the tail of MongoDB

originally published: Jun 2011I recently gave a talk at MongoNYC 2011 about using MongoDB as a messaging layer. The rationale behind doing something like this would be to maintain a log of all the messages passed between two clients. While there are many different IPC schemes available, I thought it would be interesting to build something simple on top of MongoDB using the tailable cursor feature. After giving the talk, I wanted to explore the performance characteristics of such a setup.

Before jumping into my benchmarking details, there are two important concepts to understand behind using MongoDB for message passing.

The tailable cursor gets its inspiration from the tail -f command in unix systems. For those unfamiliar with what that does, the idea is to open a file, listen for new additions to the end of the file, and print those. The program does not terminate when it reaches the end of the file, instead, it waits for more data. Using this approach, a simple message queue can be created with MongoDB. A producer creates messages and inserts them into MongoDB and then a consumer(s) is able to read those messages. While this can be simulated by keeping track of document IDs (in MongoDB and other database systems), in MongoDB the tailable cursor is actually supported server side and tracks the last returned document. This is much cheaper than having to constantly requery.

In MongoDB tailable cursors can only be opened on capped collections. This is because a capped collection is a fixed size and only allows insertions. This means that once the number of documents exhausts the collection size, newly written documents will start overwriting the first inserted documents. An important note about capped collections is that insertion order is the natural sort order. This means that when the tail cursor fetches documents, it will get them back in the order they were inserted. If you have more than one producer and insertion order matters, then you will need to either use separate collections or do your own reordering consumer side. For my examples, there is only one producer and thus natural (insertion) order is acceptable.

Now that we have some background on tailable cursors and capped collections, we can cover the benchmark setup. To perform the benchmark, I will have one producer and one consumer. The producer will get create a document of the format (Where the current time will have microsecond precision):

{ time: <current time in seconds> }The producer will generate 100,000 of these messages and insert them into the collection. To avoid dealing with a slow consumer, the collection will be made big enough to hold all of the possible messages:

db.createCollection("messages", { size: 100000000, capped: true })The producer is a simple python application:

#!/usr/bin/python

import time

from pymongo import Connection

conn = Connection()

db = conn.queues

coll = db.messages

start = time.time()

count = 100000

for i in range(0, count):

coll.insert({ "time": time.time()})

#This generates messages at a rate of about 3,900 msg/s

time.sleep(0.0001)

end = time.time()

print("total: ", count)

print("msg/s: ", count/(end - start))The consumer is a c++ client modeled after the default c++ tailable cursor example on the MongoDB page. It gets the system time upon reading a document and computes the latency between insert and read. The consumer is started before the producer:

#include <sys/time.h>

#include <mongo/client/dbclient.h>

using namespace mongo;

int main(int argc, char* argv[])

{

DBClientConnection conn;

conn.connect("localhost");

// minKey is smaller than any other possible value

BSONElement lastId = minKey.firstElement();

// { $natural : 1 } means in forward capped collection insertion order

Query query = Query().sort("$natural");

cout << "loc,val" << std::endl;

uint32_t i = 0;

struct timeval tv;

while( true ) {

auto_ptr c = conn.query("queues.messages", query, 0, 0, 0,

QueryOption_CursorTailable);

while( true ) {

if( !c->more() ) {

if( c->isDead() )

break;

sleepsecs(1);

continue; // we will try more() again

}

const BSONObj& o = c->next();

lastId = o["_id"];

const double time = o["time"].Double();

gettimeofday(&tv, NULL);

const double curr = tv.tv_sec + tv.tv_usec / 1000000.0;

cout << i++ << ", " << curr - time << endl;

}

// prepare to requery from where we left off

query = QUERY( "_id" << GT << lastId ).sort("$natural");

}

return 0;

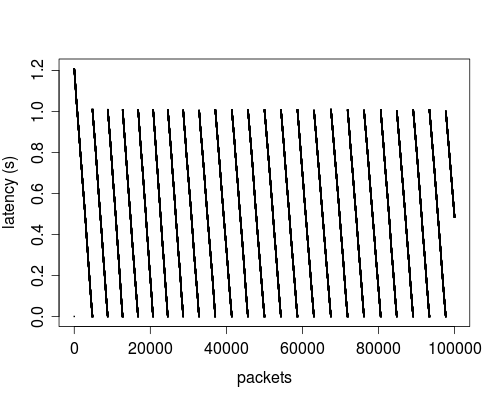

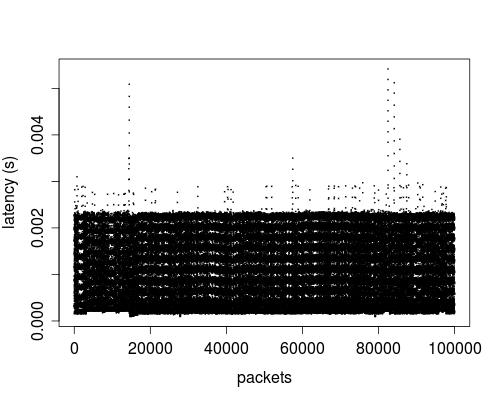

}Running the consumer/producer pair generated the following latency graph:

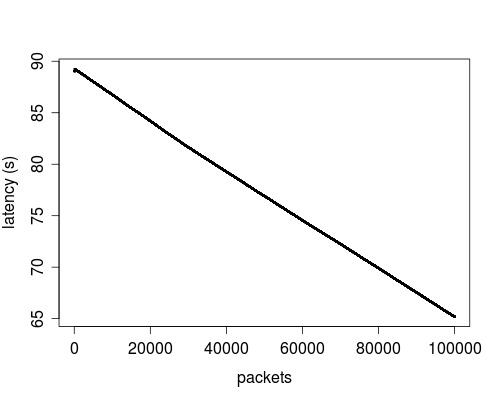

The graph is not lines, but actually 100,000 points that represent the N-th packet versus the latency (read time - write time). The above graph has a standard deviation of: 0.29693s. While these results are not horrible, the sawtooth nature of the graph would indicate that there is something strange going on and that ideally, we can do much better and decrease the latency. I ran a simple consumer (without clearing the producer data) to see if the bottleneck was in the write side or read side:

Because the read only graph is essentially linear, it means that the consumer has no problem in reading all of the data if it is available and likewise, the producer did not have problems inserting the data. (The latency is irrelevant here as the data was inserted before the consumer had to read it). So given the above graph, we know the consumer can handle reading the data consistently if it is available, so the sawtooth pattern must emerge from what happens when new data is being inserted.

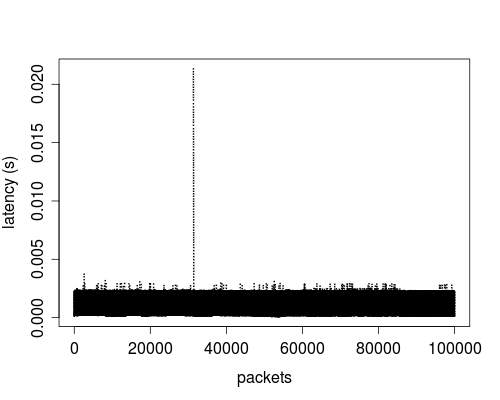

Taking another look at the Default C++ consumer graph, I noted that the consumer only goes back to ~1s latency when the previous latency was almost 0. This information, along with the c++ code which contains a sleep for 1 second was the aha! moment. When there are no more documents to read, the client waits for new documents to show up. Unfortunately, instead of being woken up when new documents are available, the default example uses a simple poll. This is expensive if our goal is to minimize latency. To test my theory I removed the sleep statement from the code and ran the consumer/producer pair again:

This method produced a standard deviation of 0.000739s. However, this is not the end solution as it has one major problem; it uses a tight loop which causes high CPU load locally and worse yet, thrashes the mongo server. Looking over the c++ driver API I found an interesting query option: AwaitData defined to: "If we are at the end of the data, block for a while rather than returning no data. After a timeout period, we do return as normal."

The AwaitData option sounded like just the thing I needed. I modified the query code to the following:

auto_ptr c = conn.query("queues.messages", query, 0, 0, 0,

QueryOption_CursorTailable | QueryOption_AwaitData);It is important to note that this causes the "more" cursor method call to block for a short time. If you cannot afford to block, this will not be a solution for you (see conclusion about some thoughts about evented systems)

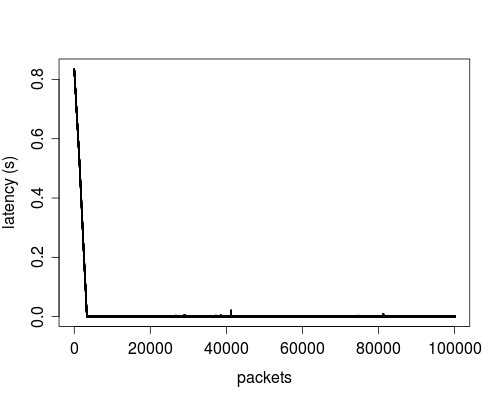

And sure enough, when there were no more records to read, the local CPU would not spin. Yet I still noticed a problem. Since I start my consumer before the producer, I found that a bunch of re-querying was happening until the first record was inserted. This is due to a "dead" cursor. When the capped collection is empty, MongoDB does not keep a cursor open server side and thus the whole "tail" process never starts until at least one record is available. Given that I did not want to spin the local CPU or thrash the server, I inserted a sleep before the "break" when the cursor was "dead". This would cause a requery every 1 second until a cursor could be created (at least 1 record was inserted). While this did solve the spinning CPU problem, I found this solution caused a high initial latencies because of the sleep before the query:

Once the initial query happened, and a valid cursor obtained, then further queries were not needed and the latency remained very low. However the start up latencies were poor because we could be anywhere in the 1 second sleep before we are able to re-query.

To solve this problem, I used a dummy document to prime the collection and cursor. Given that even with a single document, a cursor would be created server side and the client would no longer have to query waiting for a valid cursor. While this solution is also not optimal, it does avoid having to keep querying the database in hopes of obtaining a valid cursor. So here with all the pieces in place (AwaitData, dummy document, and sleep before query):

This produced a standard deviation of 0.000662s, and never spun the CPU. The final c++ client code to produce this result (just the outer while loop):

while( true )

{

auto_ptr c = conn.query("queues.messages", query, 0, 0, 0,

QueryOption_CursorTailable | QueryOption_AwaitData);

while( true ) {

if( !c->more() ) {

if( c->isDead() )

{

// this sleep is important for collections that start out with no data

sleepsecs(1);

break;

}

continue;

}

const BSONObj& o = c->next();

lastId = o["_id"];

const double time = o["time"].Double();

// handle the dummy document {time: 0.0}

// yes, not a great comparison for doubles, just an example

if (time == 0)

continue;

gettimeofday(&tv, NULL);

const double curr = tv.tv_sec + tv.tv_usec / 1000000.0;

cout << i++ << ", " << curr - time << endl;

}

// prepare to requery from where we left off

query = QUERY( "_id" << GT << lastId ).sort("$natural");

}You can see how I bypass the dummy document used to prime the cursor as an example. I ran a similar consumer/producer test with no time delay on the producer (producing ~24,000 msg/s) and also obtained similar results with a standard deviation of 0.000753s.

Conclusions

Given the above latency measurements, I found that MongoDB tail cursors and capped collections performed much better than I expected. I was hoping for latencies in the 10 to 100 millisecond range but instead often got sub millisecond latencies for standard deviation with peaks of 5 milliseconds for the last run. Depending on your definition of "low latency" using MongoDB for basic message passing is quite viable and gives the added benefit of logging all of the passed messages for things like replay or catch up (if you have sequence numbers).

In performing this benchmark I encountered some pain points. The biggest one that may lead users astray is the incomplete example on the mongodb.org page (as of this writing). It does not mention the very necessary AwaitData flag, and also incurs a high latency due to the use of sleep.

Another problem (and something I consider a bug) is the behavior when there are no items in the collection. Depending on your use case and consumer/producer startup times, this may be a hidden issue that is hogging CPU time until a valid cursor is created. From my point of view, a valid cursor should be created immediately (even with no documents) that can then behave properly under the AwaitData condition.

And finally, it would be nice to expose an API that allows the c++ client to epoll (or some other notification scheme) when new documents are available. Since with the AwaitData call the "more" cursor method blocks for a bit, this becomes very unsafe in event driven systems which should not be blocking (or any system that should not block). Since there is a socket underlying the connection to the DB, this seems like a reasonable addition that would solve such a problem.

Additional Notes

All testing was done on a Core i7 920 running Ubuntu 10.10 using an SSD as the storage medium. I used the latest of the MongoDB master github branch as of June 9th.

Initially, I tested a simple python consumer, but it too suffered from the sleep problems and did not expose query options in the same way the c++ driver did. I stuck with the c++ driver as an example given the clarity in demonstrating the various gotchas in doing the benchmark.

I toyed around with the node-mongodb-native driver and think that the "streaming" aspects could make the callback API work a bit better but would need to be flushed out more with how the GET_MORE operation to the server is handled. I found that I could lock up the server if I was not careful with how many GET_MORE ops were being sent for the cursor.